by Brighid Biehl ’24, October 25th, 2022

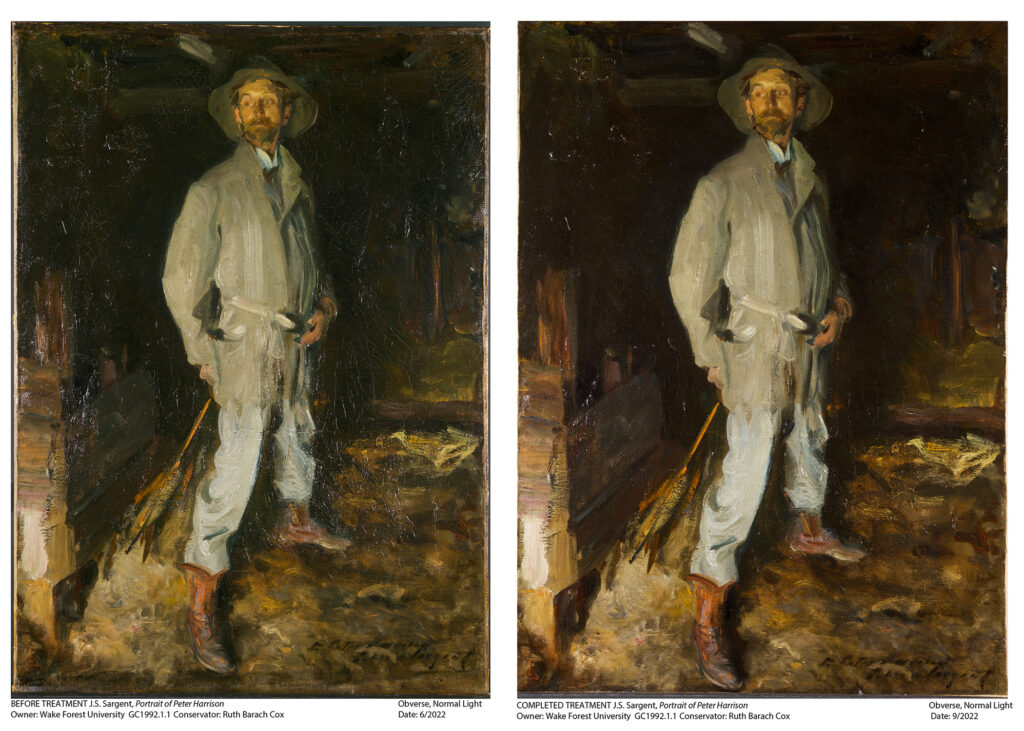

Ruth Cox is an art conservator in Durham and recently completed the conservation treatment of a John Singer Sargent painting from the WFU art collection. The painting is an undated portrait of Peter Harrison. The Sargent painting has been displayed in the president’s house and due its visual condition and environmental factors in the house, Ruth was asked to assess its condition.

Conserving a painting takes months and requires impeccable attention to detail.

With only a few weeks left in the Sargent’s restoration, I was able to meet with Ruth and learn about the process she used to conserve our painting.

Mrs. Dewitt Chatham Hanes purchased the Peter Harrison portrait from

Mirador Art services in 1976 and it hung in the Hanes home until she passed

in 1990. The painting was donated to Wake Forest by Anna Hanes Chatham,

the sister of Philip Hanes (of Hanes art gallery) in 1992. The painting has

since resided in the president’s home which used to be the Hanes family

home.

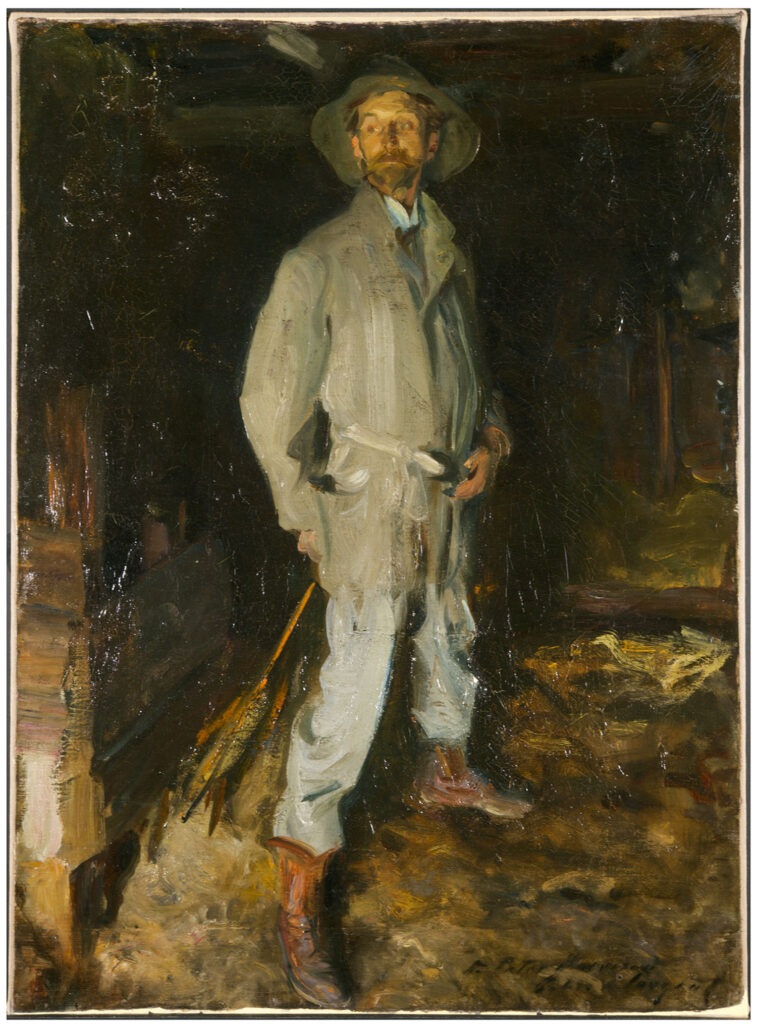

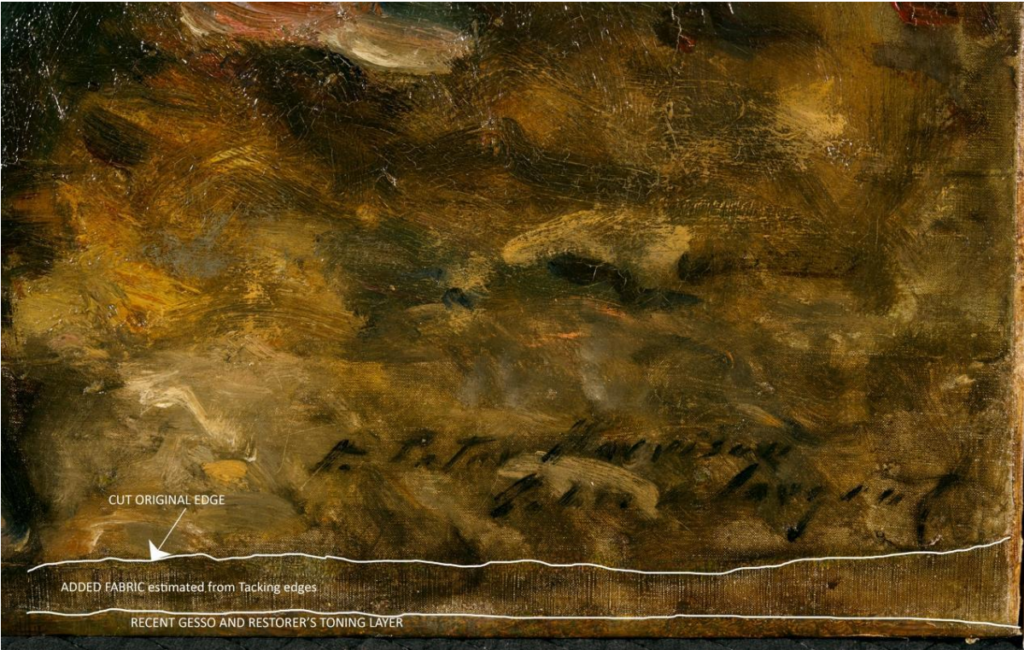

Upon initial examination, Ruth found some issues concerning the painting’s condition, such as cracked paint and oxidized old varnish as well as dust and grime that were found on the surface of the painting. Secondly, a piece of the vertical tacking edge was attached to extend the truncated bottom of the canvas used by John Singer Sargent. This was a very curious addition to the artwork and Ruth had to do some research to understand why it was there and what to do with it during the restoration process.

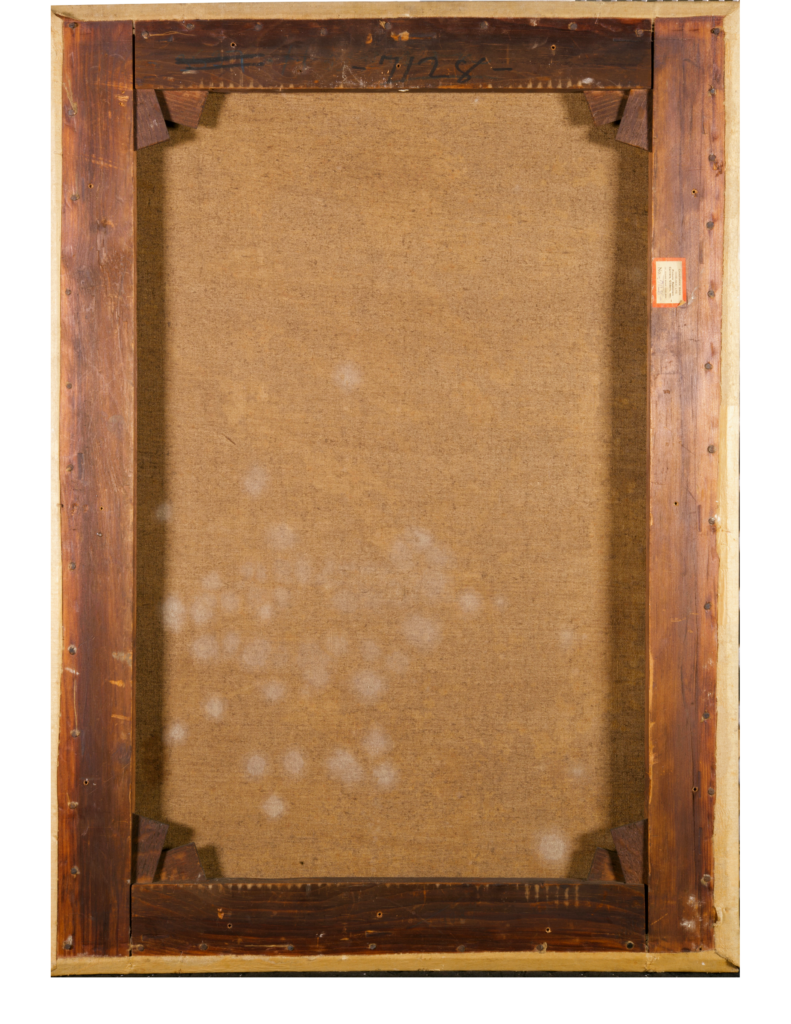

Lastly, the back of the canvas had an astounding amount of mold. The conservator surmised that the mold growth was due to humidity fluctuations in the house. Mold spores are active in higher humidity. The animal hide glue that was used to adhere a new canvas to the reverse of the original fabric provided a ‘yummy’ source of food for mold growth. After examining the artwork, Ruth wrote up her treatment plan and quote. She was then approved to restore the painting and began to uncover the true condition of the artwork.

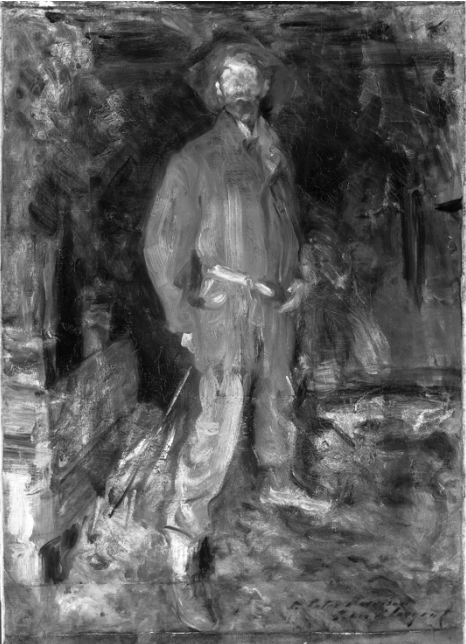

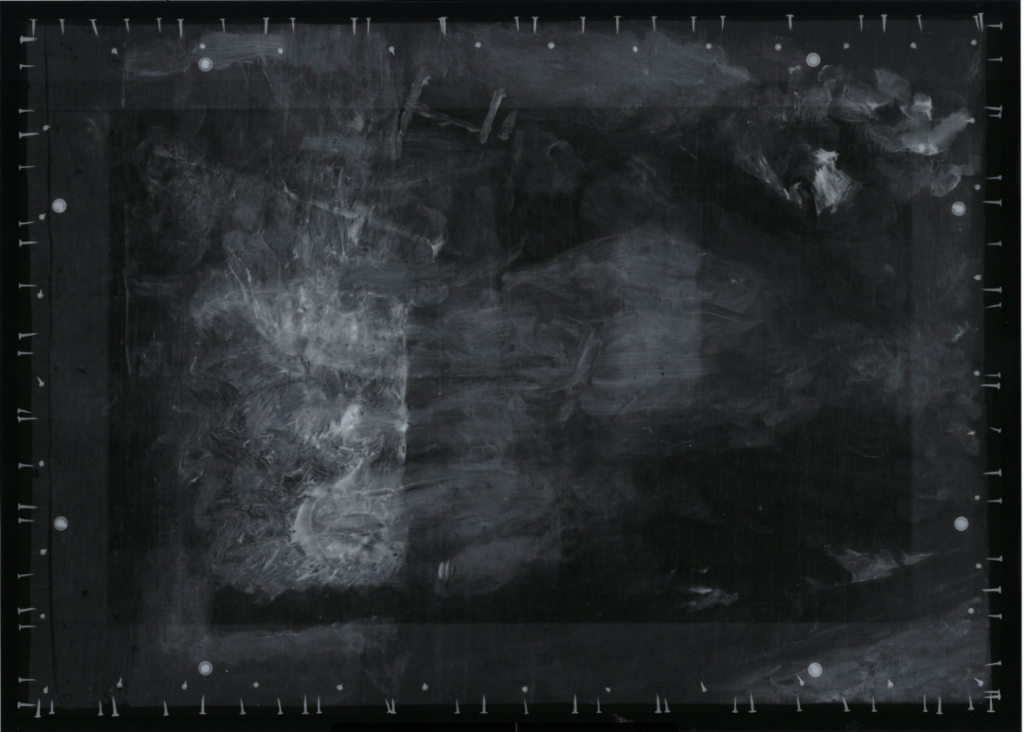

In June of this year, Jennifer Finkel, Curator and Professor at Wake Forest University, and Ruth Cox arranged for Eric Ufflemann, a Professor of Chemistry at Washington and Lee with expertise in non-invasive imaging technology, to conduct some tests on the painting. These imaging tests included IR spectroscopy, an x-ray, and XRF spectra. The analytical work let us see beneath the surface of the painting to the underlayers and also identified restorer’s and original paint on the surface. This helped them to determine that the added strip was covered with restoration not original paint. Additionally, it was clear that the canvas had been reused and that a partial composition, unrelated to the top image, lay beneath the surface.

After the analytical work was completed and the questions that necessitated

the work answered, Ruth started the conservation treatment. She started her

treatment process by deactivating the mold on the canvas reverse.

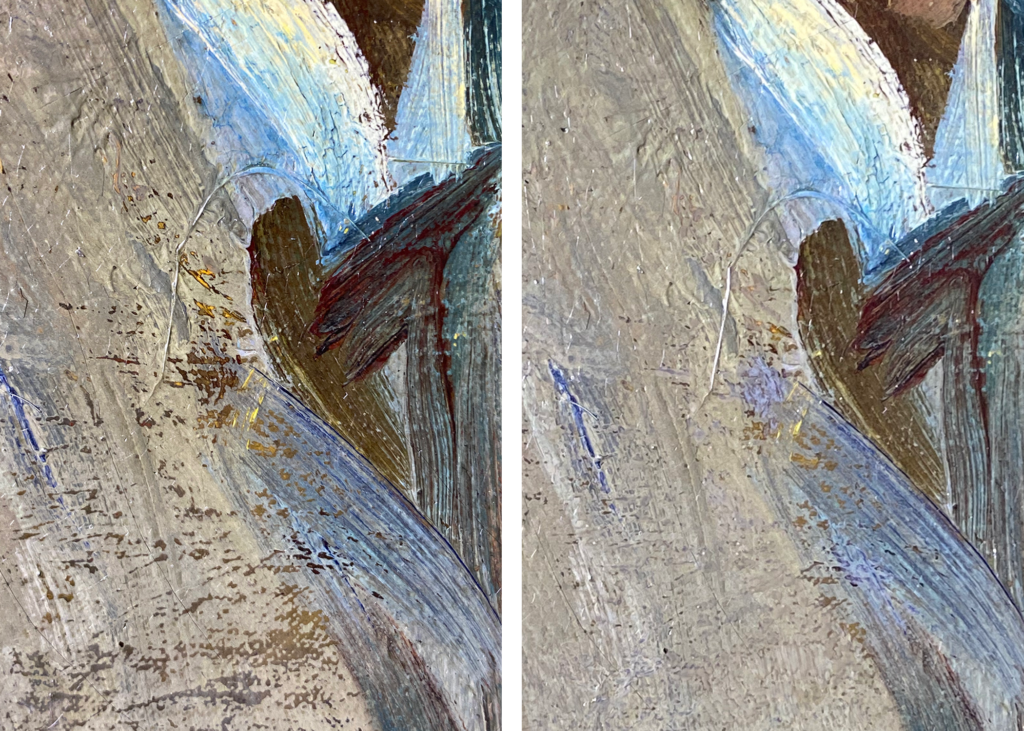

It was now time to remove the grime layer, multiple varnish layers and old

restorations. As cleaning progressed and the discolored old resin and old

restorations were removed it was possible to see under the microscope

bright colors that were unrelated to the top composition. These were visible

in wide aperture cracks and losses in the top paint film. This was a very

interesting find and the x-ray revealed more. The x-ray showed elements of

an earlier composition underneath the current painting.

Ruth conjectures that while Sargent was visiting Switzerland on holiday in

September of 1909, he decided, on the spur of the moment, to paint his

friend, Peter Harrison, and reused an unfinished canvas to do so. The

underlying composition may be a nascent landscape with either a figure or a

waterfall. This may explain the additional variety of colors not shown in the

top painting. Although there are hints of sky blue, orange and definitely white within the painting, the precise composition of the underlying image remains

a mystery.

Now that the mold was inert, the various varnish layers were removed, and a

temporary varnish put on the picture structural work could begin. Ruth

hypothesized that the mold had grown due spikes in high humidity activating

the mold growth which fed on the glue used to line the canvas. As a result,

she knew the old linen lining and adhesive would need to be removed from

the back of the original canvas. The old lining fabric was peeled off the

reverse of the original canvas, and then Ruth used a scalpel to very gently

scrape the bulk of the glue off of the original canvas reverse. This was a time-

consuming process due to the inconsistencies in the glue’s application and

fragility of the handkerchief weight linen canvas. The final glue residues were

removed from the original canvas using a super-absorbent felted polymer

infused with solvent. The canvas was lightly humidified overall to remove any

planar deformations and placed under a steel plate and weighted.

After removing the mold, Ruth dealt with the issue of the extended piece of canvas under Harrison’s toe. Ruth inferred that this strip of canvas was added to the work by a previous restorer in order to reuse an existing frame that was larger than the canvas.

The XRF spectra analysis, which is used to help determine whether similar

pigments were used at areas of retouching compared to the original paint

layer, confirmed that the canvas piece on the bottom of the painting was

added by a previous restorer and not original to the work.

After consultation with the Curator of Wake Forest Art Collections, it was

decided that the extra bit of canvas should be removed in order to restore

the work as closely as possible to its original form. The extended piece of

canvas under Harrison’s toe was easily detached from the original having

only been secured with a water-soluble gesso. Ruth conjectured that this

strip of canvas was added to the work by a previous restorer possibly to

reuse an existing stretcher that was slightly larger than the canvas. Markings

on the stretcher attested to its previous use as a support for a different

picture.

Now that the canvas reverse was cleaned, and the format adjusted the

painting was re-lined onto a stable woven acrylic fabric that is not responsive

to fluctuations in relative humidity. With the original canvas stabilized Ruth

restretched the lined canvas onto a new custom-made stretcher.

The very last treatment phase was addressing the aesthetic issues. The

temporary varnish was removed and replace it with a saturating, readily

reversible resin coating. The wide aperture cracks and losses, where

necessary, were filled with a reversible synthetic gesso. These fills and

pinpoint losses were finally inpainted with reversible retouching paints. Not

every loss was inpainted. As soon as a passage ‘read’ properly she would

address another area of damage until the entire composition pulled together

visually. One of the main tenants of conservation is that every material used

can be easily removed if needed in the future. Retouching such as that done

on this beautiful work of art is easily seen using an ultra-violet light lamp.

One of the key values of being an art restorer is to ensure that everything done to a work is reversible and can be detected by another conservator. Ruth is able to hold a black light up to the canvas and see all of her in-painting. Also, the glue and varnish she uses can be cleaned away with the proper solvents. In order to preserve the history and style of an artwork, it is important never truly to change the work. One must always work with the artist and work’s best intention in order to complete a restoration. Each work is a mystery, and the restorer must use clues to solve its puzzle. That is the beauty of restoration, to preserve history and solve problems.